I. Origins: The Salamanca School

Long before the Enlightenment or Adam Smith, the roots of libertarian thought began in the School of Salamanca — a 16th-century movement of Spanish theologians who applied Scholastic philosophy and natural law to questions of economics, morality, and politics.

Figures like Francisco de Vitoria, Domingo de Soto, and Francisco Suárez argued that individuals possess natural rights derived from God and reason, not from the state. They defended private property, voluntary exchange, and the moral legitimacy of profit, while condemning coercion and state monopolies.

In essence, Salamanca scholars laid the groundwork for the subjective theory of value, free markets, and individual liberty — ideas that would reemerge centuries later in the Austrian School of Economics.

II. From Classical Liberalism to Mutualism and Anarchism

The Classical Liberals of the 18th and 19th centuries — thinkers like John Locke, Adam Smith, and Jean-Baptiste Say — secularized and expanded these ideas. They defended limited government, property rights, and the rule of law.

But as industrial society matured, new radicals emerged who saw liberty not only as freedom from the state but from all forms of hierarchy — including economic and social domination.

This is where mutualism, articulated by Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, came in: a belief in voluntary cooperation, free markets without privilege, and a stateless order based on reciprocity.

In this way, anarchism can be viewed as the logical extreme of classical liberalism — pushing the principles of self-ownership and non-aggression to their ultimate conclusion.

III. The Rebirth of Salamanca: The Austrian School

In the late 19th century, Carl Menger, followed by Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk and Ludwig von Mises, rediscovered and refined many Salamanca insights.

The Austrian School revived the subjective theory of value, emphasizing that value originates in individual human action and choice — not labor or utility curves.

Austrians also championed methodological individualism, entrepreneurship, and spontaneous order — continuing Salamanca’s legacy of moral economics rooted in human dignity.

While both the Austrian and Chicago schools defended markets, they diverged profoundly. The Chicago School (Milton Friedman, George Stigler) embraced positivism and mathematical empiricism, seeing economics as a predictive science detached from ethics.

In contrast, Austrian economists grounded their analysis in praxeology — the logic of human action — and tied economics inseparably to moral philosophy and natural law.

For this reason, the Chicago School is not properly “libertarian” in the moral sense: it justifies markets on efficiency, not on justice or voluntary cooperation.

IV. Rothbard and the Synthesis: Anarchism Meets Austrian Economics

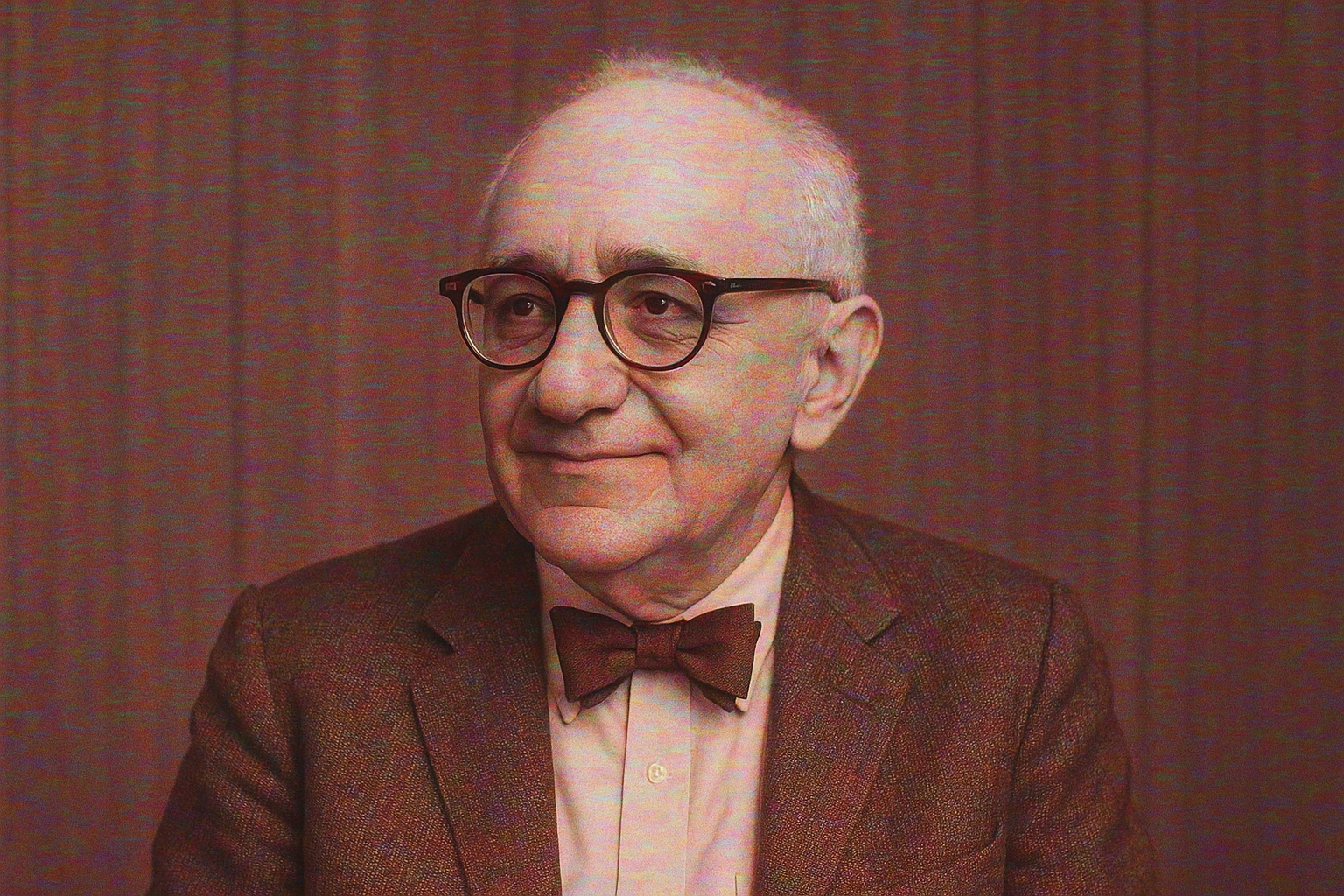

It was Murray Rothbard who fully synthesized the libertarian tradition.

Drawing from Mises’ economic logic, Lockean natural rights, and Proudhon’s stateless ideal, Rothbard created Anarcho-Capitalism — a vision of society where all services, including law and defense, could be provided through voluntary exchange and private institutions.

Rothbard’s genius lay in re-moralizing economics: he argued that liberty is not merely efficient, it is right.

He rejected the compromises of classical liberalism — minimal states, constitutions, or welfare systems — as inconsistent with the non-aggression principle.

Thus, Rothbard completed a historical arc that began with Salamanca: a return to natural law ethics fused with modern economic science.

V. Left and Right Rothbardianism

After Rothbard’s death, his intellectual heirs diverged into two broad tendencies:

- Left-Rothbardians emphasize anti-corporatism, mutual aid, decentralized communities, and cultural tolerance. They trace their roots to the radical individualists of the 19th century — Benjamin Tucker, Voltairine de Cleyre, and Herbert Spencer — blending Rothbardian economics with left-libertarian social ethics.

- Right-Rothbardians, on the other hand, stress property rights, traditional social orders, and natural hierarchies emerging from voluntary association. This stream evolved through thinkers like Hans-Hermann Hoppe, focusing on cultural conservatism and private governance as extensions of liberty.

Both sides share the same core foundation — non-aggression, voluntaryism, and the Austrian framework — but diverge on the social and moral expression of a free society.

VI. Conclusion: The Arc of Liberty

From Salamanca to Vienna, from Proudhon to Rothbard, libertarianism has been less a static doctrine than an evolving conversation about freedom.

It has passed through theology, philosophy, and economics — yet always returned to the same central conviction:

that no man or institution has the moral right to rule another without consent.

Libertarianism, at its heart, is not simply an economic theory or a political position — it is a moral vision of the human person as a self-directed being, whose dignity demands liberty.

Leave a Reply